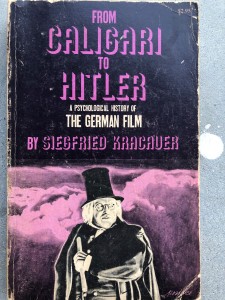

It’s funny with movies that we often come back for more of the same, whether it be a genre, a director, actors, a franchise, or whatever combination fits our mood and the current availability of product. But there is another side to it: the weird thing is movies come back to us too, seeking us out but in a quite different way from the obvious marketing, rebooting, rehashing modes that are so familiar aspects of their enticement industry. I am referring to the uncanny way in which movies (and television) must in some way connect to our contemporary world and the cultural imagination that underpins it; the way they must offer something like the feeling, in the best of them, that what we are watching exists on the crest of the emergence of a reality that is both founded on ours and one that expresses a future that is plausibly evolved from it. Which is to say they are, more often than we might suppose, aspirationally prophetic. And that leads us to the most famous work of film theory on the subject, Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of The German Film (1947).

A crude statement of its thesis is that one can see, in the German cinema of the 1920s, portents of Nazi totalitarianism of the 1930s; these portents are expressed in such things as character, plot, settings, styles and so on. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Weine, 1920) is the exemplar, because its central character Caligari – a showman who seeks permission to present his somnambulist exhibit, Cesare, at a local fair – is treated rudely by the town bureaucracy and the slight comes to stand for all that is broken with society. Caligari unleashes Cesare on the town who murders and kidnaps in an odd kind of revenge; all this within a bizarre framing narrative (about which there is much dispute and discussion). But the main point is that the film points to a kind of rage baked into the world that finds expression in civil terror, murder, disruption. Anton Kaes’s brilliant study, Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Culture and the Persistence of War (2009) further thickens the theory, reminding its readers of the real presence of traumatized war veterans on the streets of Germany during the 1920s, where ‘somnambulist’ movements and gestures were plausibly symptoms of shell shock and other forms of war trauma. Cesare would be a recognizable figure, however fantastically German Expressionist style encased him.

Joker is similarly prophetic although I should emphasize that it is not a prophecy about the coming of totalitarianism in the USA (in this matter I agree with the Marxist writer, theorist and activist C.L.R. James in this great book American Civilization (1950): ‘…the force which will be needed to impose a totalitarian state regime upon the American people does not exist and cannot be constructed.’; but also his statement that, ‘every fundamental aspect of the totalitarian state is an adaptation by tyranny to the deepest social needs of the modern age, to needs which can be clearly discerned in the democratic countries and nowhere more than in the United States.’) But before we can say why it is prophetic some clearing out of the obvious needs to be said.

Most obviously is its debt to two of Martin Scorsese’s movies, Taxi Driver (1976) and The King of Comedy (1983), one that is made as clear as waving a signpost above one’s head on a crowded city street by the casting of Robert De Niro as cheesy talk show host Murray Franklin. It is the former that is most present in the sensibility and tropes of Joker. Scorsese’s film combines two kinds of plot, the ‘worm-turns-revenge-of-the-weak’ kind, and the de-dramatized, slowed kind most obviously taken from Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951). [Film researcher, programmer and filmmaker Peter Thomas has written a brilliant thesis on this.] Travis Bickle keeps a journal, narrates parts of the film, woos a woman clearly with no clue about his pathology, and works as a taxi driver among men who also have no idea of the catastrophic alienation he is experiencing. Similarly, Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), keeps a journal, woos (at least we think he does) a woman way beyond his station, and works with others who have no idea how dangerous he is becoming. But there are important differences. Scorsese’s films are works of art although they are not works of genius: it seems that after The King of Comedy the director floundered with an overwrought and overthought sensibility, only recovering flashes of talent largely supported by the twin pillars of fine acting and strong genre (say, in Goodfellas, Casino, Cape Fear, The Departed). Taxi Driver in particular is saturated with the literary and cinephiliac sensibility of its screenwriter Paul Schrader and is keyed to expressing a severely isolated urban experience where violent rage is the necessary ‘decisive moment’ where redemption may lie (and in this sense it absorbs some of the writing of Franz Fanon).

Joker plays it differently. Whereas a plausible originating trauma for Travis’s pathology lies in his experiences in Vietnam (as with Frank Booth in Blue Velvet), Arthur’s lies in what is now the hegemonic motivating experience of most fiction: childhood abuse. The trauma that the narrative he believed and remembered was a fiction in itself (bad enough that it was) and is in fact a cover for something even worse is the plot pivot around which the film begins to show us this character’s reinvention of himself. As with Bickle’s murder of a bodega robber early in Taxi Driver, Arthur’s first brush with violence is not in itself sufficient to propel him into the dark heroism that completes his journey. For that to happen he needs the rest of the world to come to the party. That this can only happen through television is because the film is clearly set in 1981 (the fact that Arthur can smoke inside any building is an early indicator of this) a point underlined by a shot of a cinema which is showing Blow Out and Zorro: The Gay Blade both released in July of that year. So even though this is before the internet and its sub-cultural warfare (so eloquently analyzed by Angela Nagle in her book Kill All Normies (2017)), Arthur’s effect on the populace of Gotham expresses the sensibility of that war today, its infiltration of our cultural imagination. More than that, the elegant representation of inner via the outer is gracefully presented not exclusively in moments of facial intensity or dialogue, but through sheer performance. The pulling up of lips to confect a smile (a direct reference to another tale of child abuse, D. W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) with Lillian Gish’s Lucy pushing up her lips with fingers to please her monstrous father), and the motioning of the body in dance-like, angled and swooping gestures.

What, then, is Joker’s prophesy? Given the radical inflation of the definition of what counts as mental illness it is plausible that many of us will sympathize with Arthur’s pain, his isolation, his fantasies of community, friendship, love and his utter implacable hatred for the slights that the rich elite inflict unthinkingly upon us like kicking garbage out of their way on the street (should they ever have the misfortune to find themselves there unprotected). The elite watch Chaplin’s Modern Times in tuxedos and gowns chuckling along. I’ve never found Chaplin funny preferring Keaton, Lloyd, Laurel, Hardy. Arthur seems to like him, for a while. And the only funny part of the movie is the ending, a standard chase gag at distance. We should cling, one would hope, to his fantasy of a normal life, of solidarity with friends, family and community. But when we’re denied that don’t be surprised when what happens next, happens.